Kristin Tollefson's Bliss

Emerging from the laurel grove, one finds oneself in a grove of another sort. Bamboo sprouts crowd up the hill in a thicket of strong stalks. Along the edge of the trail to the right is a natural quince bower, created by two lichen-encrusted specimens that have grown together in a knot of branches. Past the bower is a natural room skirted on the back and sides by the aforementioned bamboo, and carpeted by ivy.

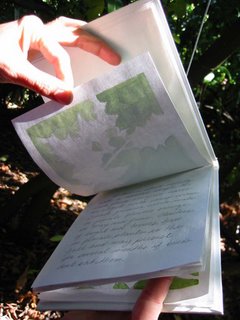

I was drawn to this space very early on in the process of looking at the site, and for many reasons considered it to be too precious, or entirely complete without my interference. And all the same, I kept returning and questioning my draw to the place. In the end, I realize I wanted to make the vastness of the site smaller and more intimate, that I wanted to reference my personal relationship with the place which includes making a special hideaway for my kids, and to call into mind the historical fact that there was a valid domestic aspect to what is now seen primarily as a derelict industrial zone.

The chair frames were salvaged from under the laurel grove next door, and woven with raw steel wire. Black wooden beads punctuate the back rest and mimic the blackened quince that I discovered beneath the ivy and propped in the bower.

"My work derives its form from the organic and constructed worlds of botany and personal adornment. Utilizing traditional fiber techniques of stitching and weaving, I build my work out of metal wire and surplus, cast-off or industrial materials; I relish the tension inherent in creating beautiful, precious objects out of ordinary components. Inspiration for my forms is drawn from sources as wide-ranging as botanical illustration, folk art, fractals, and food preservation. Simultaneously scientific and poetic, these sculptures often assemble multiple simple elements into complex wholes, addressing themes of generative and transformative processes, the value of production and attention to detail, and the dialogue between interior and exterior space.

Bliss is a space that engages the domestic and the dream. It is a place into which we retreat. It is of this earth, but not of this world."